Hidden Barriers

SuperStudio 3

Dr. David Coyles, Senior Lecturer in Architecture

Eduardo Rebelo, Teaching Fellow

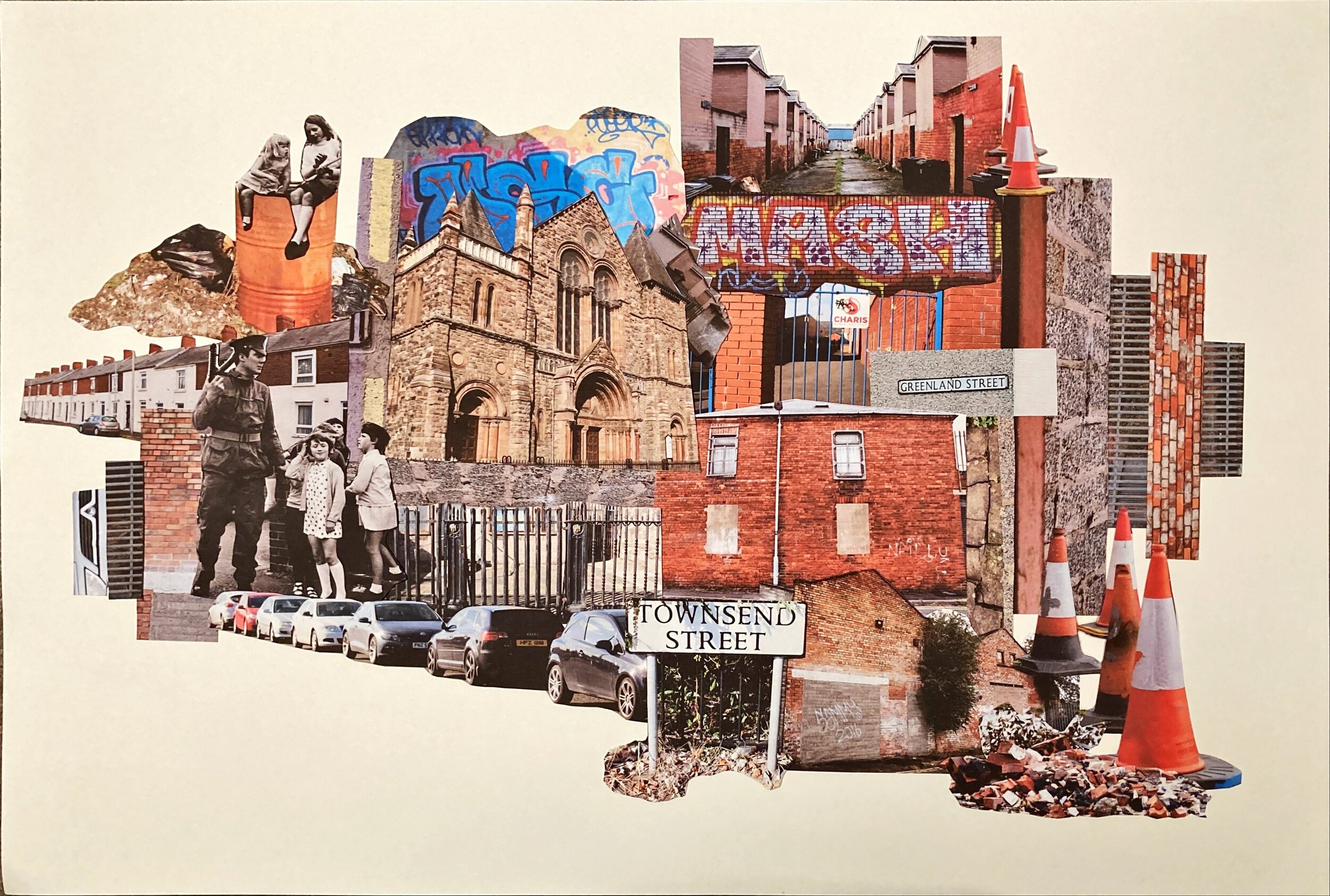

The Hidden Barriers SuperStudio examines how the processes of political, economic, military and ideological conflict shape urban space and community development. It presents students with a chance to participate in a series of investigations taking place as part of ongoing academic research funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). The studio uses this research base to explore innovative and cross-disciplinary methods of charting, analysing and mapping urban landscapes and proposing thoughtful architectural propositions.

The third iteration of the Hidden Barriers SuperStudio begins with an examination of the Westlink and the peripheral inner-city communities and urban spaces along its edges.

The Westlink is perhaps the single most dominant architectural feature in the Belfast urban area. Nothing matches its size or its physical impact. Brutal in both concept and operation, it manages to enable 80,000 vehicles to pass unhindered directly through the heart of urban Belfast. This was achieved by literally cutting headlong through the built landscape of the city and obliterating everything in its path.

The origins of the Westlink can be found in the 1964 Transport Plan for Northern Ireland which proposed a large network of new motorways stretching throughout the eastern counties of Northern Ireland. An integral part of this plan was the construction of a new Belfast Urban Motorway, a complex arrangement of elevated carriageways and link-roads that would encircle the city and connect into the surrounding motorway network at dedicated points. The advent of the Troubles in 1968-69 brought a drastic reduction to these plans. Of the wider motorway network, only the M1, part of the M2 and the M22 would be built. As for the vision laid out for the Belfast Urban Motorway, only the Westlink was approved for construction.

The Westlink endures as a complex architectural legacy of the Troubles. Despite the fact that the original plans for the Westlink date back to the early 1960s, it was (and still is) considered by many to be a deliberate security response to sectarian conflict. This can be seen in how it comprehensively and unilaterally disconnects the communities of the historically Catholic ‘Falls Road’ and the historically Protestant ‘Shankill Road’ from the commercial heart of the city.

STUDIO RESEARCH STATEMENT

Research Content and Process

Hidden Barriers considers architecture in its widest sense and our examinations are particularly interested in the less visible ways that conflict manifests itself in ‘everyday’ urban space. Whilst ‘spatiality’ and ‘architecture’ have become recognized as important dimensions of urban conflict, contemporary forms of power push our gaze towards symbolic landmarks such as Belfast’s ‘peace walls’. The Hidden Barriers SuperStudio uses Belfast as a case-study to instead highlight the fundamental role occupied by ‘everyday’ urban space and architecture. It reveals evidence of an undisclosed body of divisive architecture put in place through a confidential process of security planning between 1978 and 1985 to physically segregate and spatially fragment Catholic and Protestant communities in contested areas of Belfast. Termed by the research as ‘hidden barriers’, they are formed from ‘everyday’ roads, housing, shops, offices, factories and landscaping, and the ways in which they continue to promote division represents a crucially undervalued aspect of conflict-transformation planning. The SuperStudio examines the complex urban challenges that they pose, arguing for a re-evaluation of the role of everyday architecture and space in conflict and peacebuilding processes.

Description

Hidden Barriers considers architecture in its widest sense and our examinations are particularly interested in the less visible ways that conflict manifests itself in ‘everyday’ urban space. Whilst ‘spatiality’ and ‘architecture’ have become recognized as important dimensions of urban conflict, contemporary forms of power push our gaze towards symbolic landmarks such as Belfast’s ‘peace walls’. The Hidden Barriers SuperStudio uses Belfast as a case-study to instead highlight the fundamental role occupied by ‘everyday’ urban space and architecture. It reveals evidence of an undisclosed body of divisive architecture put in place through a confidential process of security planning between 1978 and 1985 to physically segregate and spatially fragment Catholic and Protestant communities in contested areas of Belfast. Termed by the research ‘hidden barriers’, they are formed from ‘everyday’ roads, housing, shops, offices, factories and landscaping, and the ways in which they continue to promote division represents a crucially undervalued aspect of conflict-transformation planning. The SuperStudio examines the complex urban challenges that they pose, arguing for a re-evaluation of the role of everyday architecture and space in conflict and peacebuilding processes.

Research Questions

The overarching aim of this research is to effect material change in the community life of some of Belfast’s most deprived urban areas. The studio therefore places an emphasis on helping to help make the contemporary effects of what we term ‘Hidden Barriers’ more visible, so that we can begin to have meaningful discussions and debates about their continued presence and impact. This suggests three questions:

What do these Hidden Barriers look like?

Where are they located? What urban areas are affected? What specific types of buildings, structures and spaces are involved?

What do communities have to say about this architecture?

What are the experiences of residents? What problems do they perceive? What changes would they like to see?

How can this research inform the related and relevant policy discussions?

What barriers and forms of physical division are currently under the scope of the ‘united community’ policy umbrella and which are not?

Methods

Our investigations employ multidisciplinary methodologies drawn from the underpinning Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded research projects. However, there is a primary emphasis placed on the gathering of evidence through core practice-based architectural fieldwork and the related tactics of observation, drawing and model-making. These are supplemented by site-based video and photography. All investigations are typically underpinned by a mix of archival research, qualitative interviews and literature reviews.

Findings and Outlook

The research suggests three typologies of hidden barriers which act at different scales and in different ways to promote social and physical division. At the first level, there are Inter-Community Barriers. These are instances of the built environment being used on a larger scale to separate two communities that were connected through the urban fabric before the onset of redevelopment in 1977, effectively leaving them fixed and isolated as ‘single-identity’ areas. At the second level, Intra-Community Barriers are instances where the redevelopment proposals within these single-identity communities have transformed the existing network of interconnected terraced streets into spatially fragmented and disconnected clusters, creating urban areas that are extremely fractured and difficult to navigate. The third level of hidden barriers are what we call Invisible Boundaries. These barriers are not a direct consequence of the redevelopment programs or security-orientated government intervention. Rather, they are elements of public space on the periphery of other hidden barrier areas that are identified locally as a recognised ‘boundary’ between the two communities, which has evolved at a local level and become entrenched over time.

Dissemination

The research findings have informed a range of publications (Coyles 2013, 2017a, b; Coyles 2018; Coyles, Hamber and Grant 2018; Coyles, Spier and Wylie 2013; Wylie and Coyles 2018). The findings have also been the subject of international workshops and policy symposia in Detroit, San Diego, the Basque Country, Sweden and the Netherlands. In 2018, the findings were presented at the Northern Ireland Assembly Knowledge Exchange Seminar Series (KESS).

For more information on this SuperStudio, please contact David Coyles