Hidden Barriers IV

SuperStudio 1

David Coyles, Senior Lecturer in Architecture

Eduardo Rebelo, Teaching Fellow

HIDDEN BARRIERS looks at the ways in which the architecture and spaces of present-day Belfast continue to be impacted by the legacies of the Troubles, the period between 1969 and 1998 when the sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland was at its most extreme. It presents students with a chance to participate in active research investigations taking place as part of the Ulster University Hidden Barriers research programme, underpinned by a series of projects funded by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

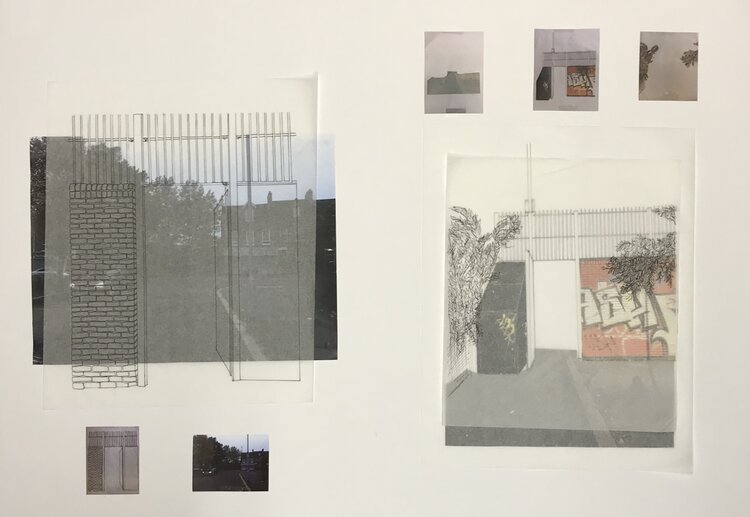

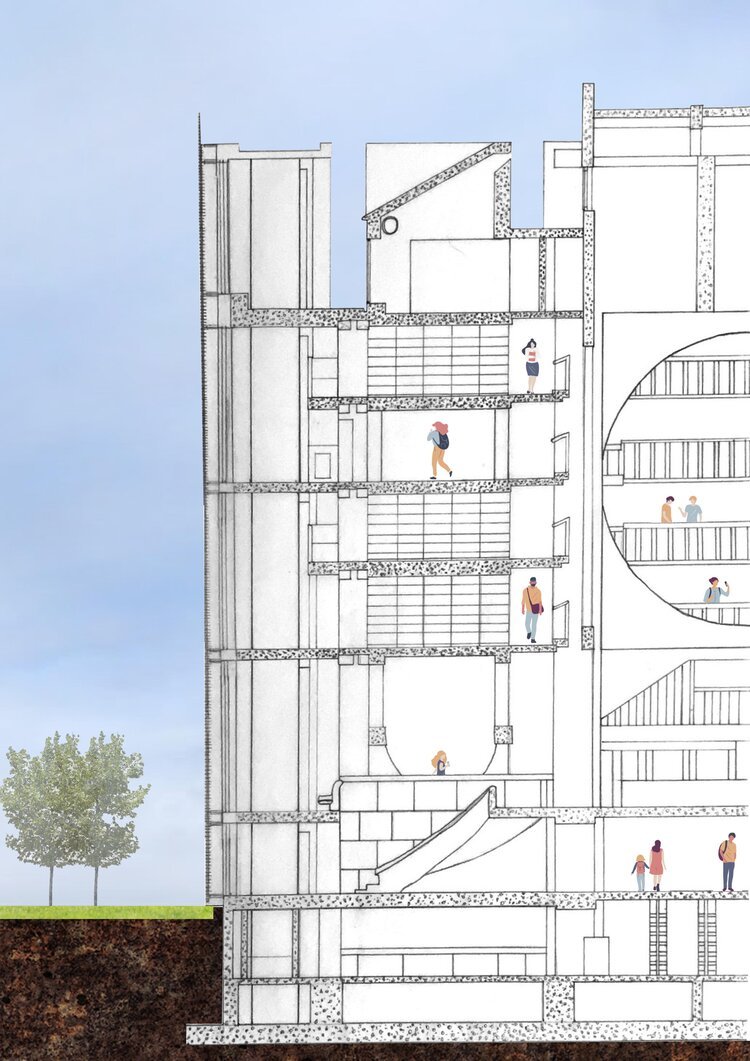

Hidden Barriers uses this multidisciplinary research base to explore innovative and cross-disciplinary methods of charting, analysing and mapping urban landscapes and proposing thoughtful architectural propositions. We make creative use of drawing, photography, video and a wide range of digital-software techniques — and we place a strong emphasis on the use of physical and digital models to communicate our design thinking, design process and architectural proposals.

Invisible Cities is the fourth iteration of the Hidden Barriers superstudio. When Calvino (1997) wrote of the Invisible Cities, this mystical collection of narratives discussed what was in fact the real city of Venice. Yet through a corpus of imaginative tales Venice is also at once the city of Zirma, of Armilla, of Baucis, of Moriana and of Argia (to name but a few). This fictional association is a deliberate provocation to establish the challenge inherent in conducting an examination of architecture created, transformed and destroyed by conflict.

Calvino’s fables are evoked through fictive rendering of myth and legend where the application of meaning is at the behest of the storyteller. The capacity for alternate (and perhaps equally valid) descriptions of architecture prompts an interesting consideration as to whether these tales were works of the imagination or, rather, adroit interpretations of Venice manifest in its bricks, stones, mortar, water and earth. In this sense a conceptual connection can be drawn with the city of Belfast.

Like Calvino’s Invisible City, Hidden Barriers theorises Belfast as a Hidden City enjoying competing and conflicting interpretations of its architecture that camouflage its full quintessence and ultimate importance. Viewed through the emotive lens of a city emerging from the Troubles which raged between 1969 and 1994, the studio discussions pertain to the imaging (not imagining) of architecture as something other than what it first might appear to be, or perhaps, something different altogether.

Cupar Way

Hidden Barriers IV investigates the ways in which the architectural legacies of conflict are often rendered invisible by alternative city narratives aimed at tourism and business. Our investigations commence by focusing on a case-study which is perhaps the most prominent line of political division within the city of Belfast; that which separates the historic Catholic heartland of the Falls Road from the historic Protestant heartland of the Shankill Road. This physical division is dominated by one of the world’s most iconic, and infamous, pieces of architecture - the Cupar Way peace wall. This massive structure, over 800m long and over 7.5m high, is almost alien-like in appearance. Yet, it has become as synonymous with Belfast as the images of the Samson and Goliath cranes that tower of the docks of east Belfast. It is the very opposite of a hidden barrier. In fact, it is undoubtedly the most visible physical barrier in the city. So much so, that it is a major stop on the various popular tours of the city that are now offered by a range of local and international tour operators. Stand at the Cupar Way peace wall for any length of time on any given day, and you will soon see the international coach tours carrying visitors who have just disembarked from one of the many cruise ships that now routinely visit Belfast. Many of these will stop at the wall and allow the passengers to walk along its length and sign their name upon the art-worn surface. Or you may see a succession of bus tours ferrying groups of sightseers up and down Cupar Way, the Falls Road and the Shankill Road. And there are always the ‘black cab’ tours, much more intimate affairs, where local guides will pull their taxi up to the kerb and give a personalised take on their knowledge of this wall.

Whilst these narratives tend to direct our gaze towards symbolic landmarks such as Belfast’s ‘peace walls’, and away from the more problematic legacies of conflict, Invisible Cities reveals the problems that this poses for genuine conflict transformation by considering conditions in present-day Belfast alongside contemporary examinations of the contrasting post-conflict cities of Detroit, USA, and Bilbao in the Basque Country.

Detroit

Once the fourth largest city in the USA and a rich and powerful hub for economic activity that centred on the automotive industry, decades of outward migration, disinvestment and social change have ravaged the city, creating images of inner-city desolation and abandonment on a scale not thought possible within the developed world. The abundance of vacant, unwanted space is such that it has become home to ‘urban farming’, with acres of crops now occupying ground that was once prime real-estate. More starkly put, the entire urban core of the city of San Francisco, USA, could be fitted within the vacant space that exists within present-day Detroit. The material visibilities of social and economic conflict remain very visible.

Bilbao & The Basque Country

The studio will also be drawing upon Cartographies of Conflict research into political conflict in the Basque Country. Particular emphasis will be placed on the ways in which post-industrial Bilbao has been transformed through long-term and considered architectural planning and development – and how the underlying cultural and territorial tensions continue to become manifest in the built environment.

STUDIO RESEARCH STATEMENT

Research Content and Process

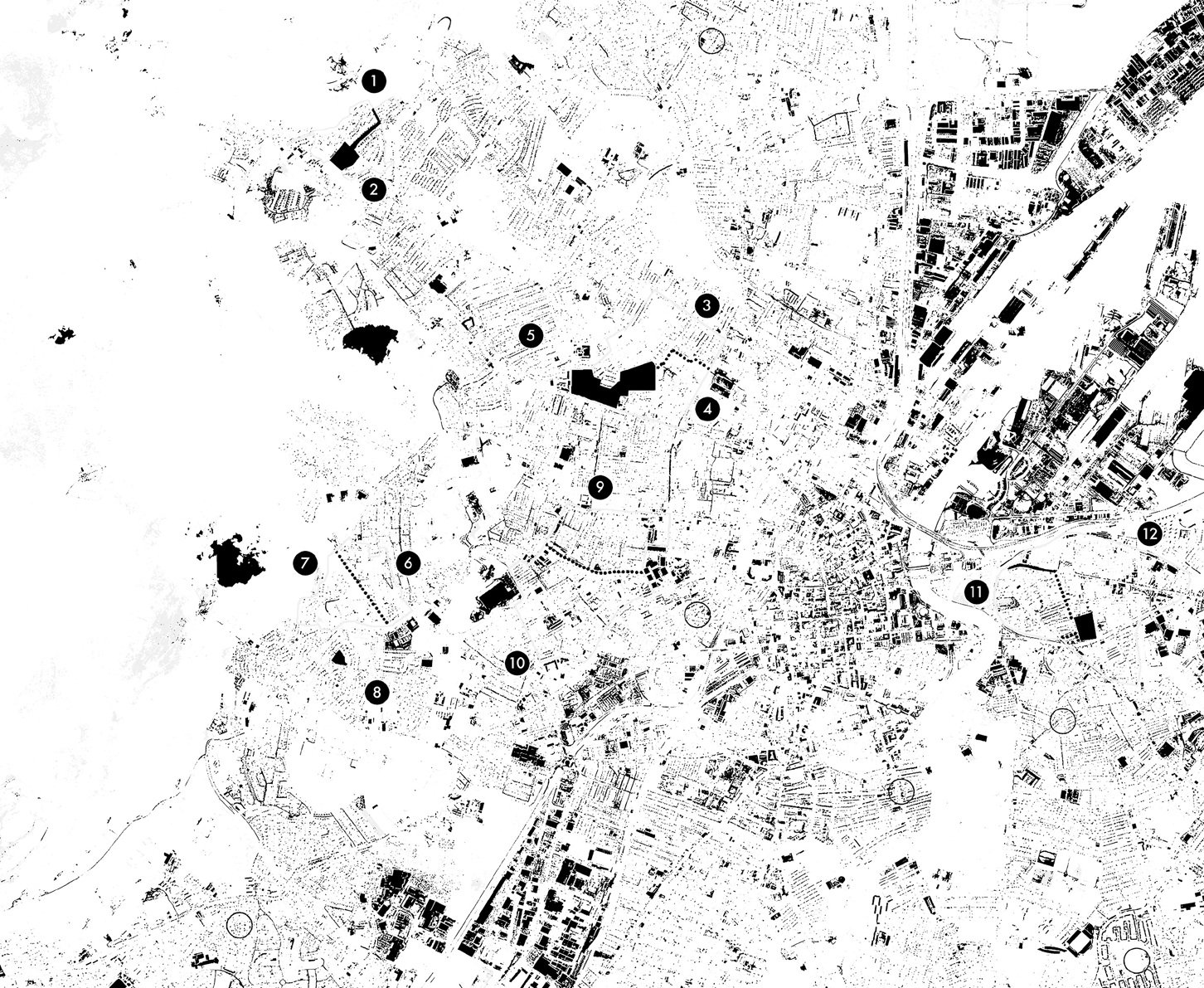

Hidden Barriers considers architecture in its widest sense and our examinations are particularly interested in the less visible ways that conflict manifests itself in ‘everyday’ urban space. Whilst ‘spatiality’ and ‘architecture’ have become recognized as important dimensions of urban conflict, contemporary forms of power push our gaze towards symbolic landmarks such as Belfast’s ‘peace walls’. The Hidden Barriers SuperStudio uses Belfast as a case-study to instead highlight the fundamental role occupied by ‘everyday’ urban space and architecture. It reveals evidence of an undisclosed body of divisive architecture put in place through a confidential process of security planning between 1978 and 1985 to physically segregate and spatially fragment Catholic and Protestant communities in contested areas of Belfast. Termed by the research as ‘hidden barriers’, they are formed from ‘everyday’ roads, housing, shops, offices, factories and landscaping, and the ways in which they continue to promote division represents a crucially undervalued aspect of conflict-transformation planning. The SuperStudio examines the complex urban challenges that they pose, arguing for a re-evaluation of the role of everyday architecture and space in conflict and peacebuilding processes.

Description

Hidden Barriers considers architecture in its widest sense and our examinations are particularly interested in the less visible ways that conflict manifests itself in ‘everyday’ urban space. Whilst ‘spatiality’ and ‘architecture’ have become recognized as important dimensions of urban conflict, contemporary forms of power push our gaze towards symbolic landmarks such as Belfast’s ‘peace walls’. The Hidden Barriers SuperStudio uses Belfast as a case-study to instead highlight the fundamental role occupied by ‘everyday’ urban space and architecture. It reveals evidence of an undisclosed body of divisive architecture put in place through a confidential process of security planning between 1978 and 1985 to physically segregate and spatially fragment Catholic and Protestant communities in contested areas of Belfast. Termed by the research ‘hidden barriers’, they are formed from ‘everyday’ roads, housing, shops, offices, factories and landscaping, and the ways in which they continue to promote division represents a crucially undervalued aspect of conflict-transformation planning. The SuperStudio examines the complex urban challenges that they pose, arguing for a re-evaluation of the role of everyday architecture and space in conflict and peacebuilding processes.

Research Questions

The overarching aim of this research is to effect material change in the community life of some of Belfast’s most deprived urban areas. The studio therefore places an emphasis on helping to help make the contemporary effects of what we term ‘Hidden Barriers’ more visible, so that we can begin to have meaningful discussions and debates about their continued presence and impact. This suggests three questions:

What do these Hidden Barriers look like?

Where are they located? What urban areas are affected? What specific types of buildings, structures and spaces are involved?

What do communities have to say about this architecture?

What are the experiences of residents? What problems do they perceive? What changes would they like to see?

How can this research inform the related and relevant policy discussions?

What barriers and forms of physical division are currently under the scope of the ‘united community’ policy umbrella and which are not?

Methods

Our investigations employ multidisciplinary methodologies drawn from the underpinning Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded research projects. However, there is a primary emphasis placed on the gathering of evidence through core practice-based architectural fieldwork and the related tactics of observation, drawing and model-making. These are supplemented by site-based video and photography. All investigations are typically underpinned by a mix of archival research, qualitative interviews and literature reviews.

Findings and Outlook

The research suggests three typologies of hidden barriers which act at different scales and in different ways to promote social and physical division. At the first level, there are Inter-Community Barriers. These are instances of the built environment being used on a larger scale to separate two communities that were connected through the urban fabric before the onset of redevelopment in 1977, effectively leaving them fixed and isolated as ‘single-identity’ areas. At the second level, Intra-Community Barriers are instances where the redevelopment proposals within these single-identity communities have transformed the existing network of interconnected terraced streets into spatially fragmented and disconnected clusters, creating urban areas that are extremely fractured and difficult to navigate. The third level of hidden barriers are what we call Invisible Boundaries. These barriers are not a direct consequence of the redevelopment programs or security-orientated government intervention. Rather, they are elements of public space on the periphery of other hidden barrier areas that are identified locally as a recognised ‘boundary’ between the two communities, which has evolved at a local level and become entrenched over time.

Dissemination

The research findings have informed a range of publications (Coyles 2013, 2017a, b; Coyles 2018; Coyles, Hamber and Grant 2018; Coyles, Spier and Wylie 2013; Wylie and Coyles 2018). The findings have also been the subject of international workshops and policy symposia in Detroit, San Diego, the Basque Country, Sweden and the Netherlands. In 2018, the findings were presented at the Northern Ireland Assembly Knowledge Exchange Seminar Series (KESS).

For more information on this SuperStudio, please contact David Coyles